The Mattress

Four months ago I set out to clear my house of clutter. For forty years I have lived in the same place, with barns and chicken coops and rooms aplenty for collecting stuff, so this is no mean task. My sage son Gordon suggested I start with duplicates.

As I gathered up my duplicates/triplicates/quadruplicates I began to see myself and my fears and sadness, cloaked in crazy, from some distance. I had three garlic presses, two blenders, three rasps, four sewing machines, two coffee grinders, four curling irons, five wire whisks, seven t-squares, and three rabbit puppets for starters. Against some projected future shortage I was holding onto dozens of sheets and blankets. I had an addiction to containers for storing things. Lots of them were empty and taking up space in the dusty and cluttered attic. Every time I opened the broom closet two or three of my six yardsticks would tumble out onto the floor.

A lover of history, I’d become the repository for lots of artifacts from our family’s past. There was a totally unorthodox baroque clock in the attic that my father, the GI, had “liberated” from a bombed-out German apartment building at the end of WWII. In my father’s eyes, the clock was magnificent, but it was actually a crazy pastiche of little portraits painted on porcelain sandwiched between furbelows of brass. It was an object that was hard to love. But it spoke of a moment in time— the end of a horrible war and my dad as a very young man. It conjured up the image of a devastated country. It no longer works as a clock. But it serves as a link to 1945 and my father, and his quirky idea of what was desirable.

There was an afghan in the attic made by my maternal great-grandmother, Granny Gordon. She knitted and crocheted miles and miles of yarn and thread into useful household objects, but this afghan is probably the ugliest thing she ever made. Chocolate brown, grass green and pale yellow, no one has ever used it or displayed it, but I have stored it since I first became its guardian. It has lived in a cedar chest in the attic where it has not seen the light of day for 40 years.

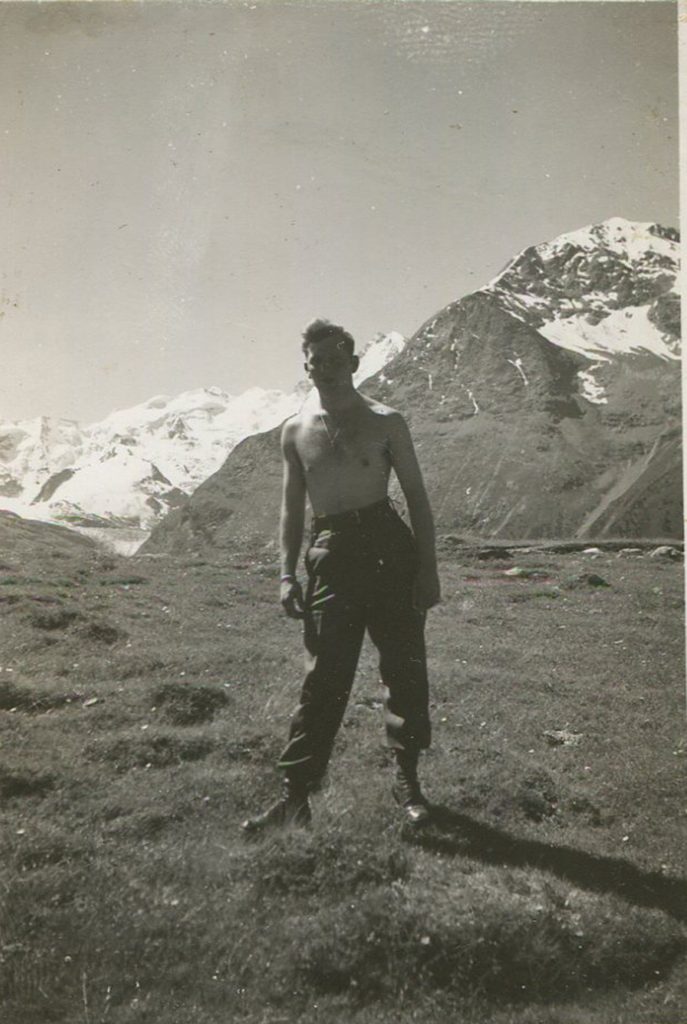

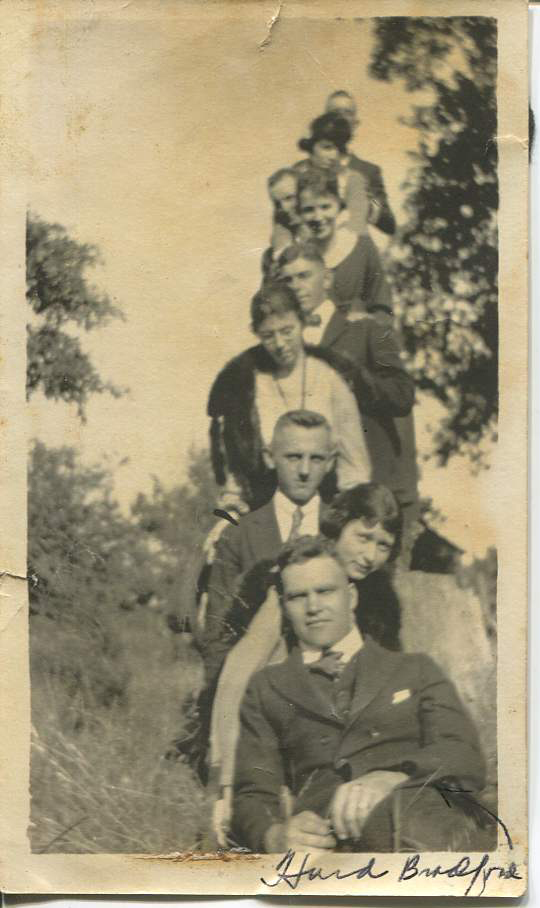

I rediscovered a box of textbooks and notebooks owned by my great uncles and my grandfather, from the early 20th century. They grew up in this house sharing the upstairs bedrooms. Two of them went off to medical school and the attic holds their chemistry notes and their drawings of microorganisms. Two of them studied agriculture and I have their drawings of plants. One studied business, and the only daughter studied to be a teacher. I’ve come to know them by examining their notes, their handwriting, the things they studied. My grandpa, Hurd Bradford, Sr. served in the Navy in WWI and there were homesick letters to his mother in a tin box. There was a naval uniform that belonged to my father-in-law, an intrepid submariner in WWII, and a painting by a great aunt who studied art in New York around the turn of the century, technically proficient but lacking any sense of the life she lived, and riddled with holes.

My mother, always a respecter of history and the bearer of many family tales, years ago handed off a goose feather mattress made by my paternal great-grandmother, Mattie Dora Worsley Staton. Grandmother Staton, as we called her, had raised the geese, killed the geese, plucked the geese and sewn this mattress. And it lay in my attic for 40 years. Mama and I both respected the hard work it had taken to make this mattress. Among my papers there is the last will and testament of another ancestor who bequeathed her feather mattress to one of her children as if it might have been a house or a car. It was, in its time, an object of great value. I asked my son, my clearing mentor, what to do with this mattress. His response was “let me think about that one”.

I told the story of the mattress to my dear friend Suzy, who also loves history and collecting, and she set me free, assuring me that the mattress was by now alive with mites and other invisible creepy things. That was all I needed to bag it up and haul it away. She suggested that I take a scrap of the ticking that contained it, and save it as a memento. I decided instead to remember Grandmother Staton by saving the mattress in prose—in digital format.

The attic holds so many stories I will never have time enough to tell them all to my sons. On some day in the future I imagine them up there, sneezing, cursing and tossing. They are, to a man, minimalists. I am, as they say, a maximalist. Never have I felt my role so powerfully as connector between the world as it has been for generations and the world as it now suddenly is. I write to lock some of it down.

Slowly, open spaces are appearing. I have driven truckloads to the dump, and station wagon loads to the Habitat store. Every week on pick-up day, my trash can is full. Freeing myself from attending hundreds of objects is a thrill. I revisit each thing. I decide what will happen to it in the Digital Age and if it’s worthy I find it a new and awkward home, or I write to lock it down.

This sounds like a wonderful treasure hunt…there is nothing wrong with having/saving more than one of a kind! Come to my house! We have dozens of duplicates…and we are blissful! Love you, Elizabeth!

I love this. Just let go of a few more things myself. It is liberating, and not easy.

This gives me courage to work on my house. I bought it in 2009 and it has only three bedrooms and one attic. The challenge is that all my pre-divorce family stuff like kids clothes and toys are in the attic, and a ton of inherited things from my parents are jammed in along with the household goods I need. I am going to begin by throwing and giving away and then organize. It’s snowing and cold so I won’t attack the attic until the spring.

Anyway, your larger challenge (mites!)is a piece of my inspiration, and the other piece is fear of Caitlin Hall’s approbation. Cait’s organization personified. Yikes, she will be here for two nights and a day in three weeks.

Quite a fine little essay–accounting for another “essay” to clear the shelves! I need to do this again and again.

i will have to do this soon enough. jay would like it to be sooner. he gave me ‘the life-changing magic of tidying up’ for christmas 🙂

Elizabeth I am right there with you. When Steve and I retired last summer, we came home to our house that we had neglected for all the years we have worked 2 & 3 jobs and owned Nomad 10 years. We started 1 closet and 1 cabinet at a time. My kids noticed immediately and suddenly I felt so much more organized and efficient even though I probably am not but it was a refreshed and renewed feeling and I loved it !

You speak the truth and describe my world in an almost disturbingly accurate picture. I myself still lack the courage to face this but thank you for sharing as it created lots of smiles and recollections.

An inspirational story! I’ll remember the mattress as I work my way through my own artifacts.

I so need to do this – I say “yes, I’ll take it, of course” to every object my mother passes along to me. Many of them I hold dear, but some turn to dust tucked into the back of closets or crammed into the attic. My attic also contains bags and boxes of stuff from my kids – at some point (probably middle school) they figured out that when I would ask them to clean up their rooms/floor/closets, they could just put everything in a box and run it up to the attic, and I would never notice. As I brought down Christmas decorations I grabbed a box… filled with hair clips and bows and little plastic frogs and lizards from my daughter’s “cleaned up room” years ago. Of no value to anyone except me, who has memories of learning how to deal with a little girl’s long hair many years ago.